What is Celadon?

"Autumn wind and dew, the Yue kiln fires up, stealing the green hues of a thousand peaks."

The Tang Dynasty poet Lu Guimeng aptly described the beauty of celadon with the image of the green peaks and valleys, capturing the essence of its color and luster.

Elegance and subtlety are the hallmarks of celadon, and when literati and scholars use celadon to drink tea, the wisps of tea aroma add to the ethereal feeling.

So much so that they have given various elegant names to different shades of celadon, such as "Mugwort color," "Secret color," "Rain clears to blue skies," "Plum green," "Pink celadon," and so on. These words and phrases describe the different hues of celadon.

A collection of representative ceramic wares from various kilns. The top row, from left to right, includes:

- A Ru kiln sky blue oval narcissus bowl, housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

- A Yaozhou kiln blue glazed bowl with carved three fish pattern, housed in the Yaozhou Kiln Museum.

- A Yue kiln Northern Song Dynasty celadon peony pattern powder box, housed in the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Museum.

The bottom row, from left to right, includes:

- A Longquan kiln celadon tripod censer, housed in the Hangzhou Museum.

- A Wuzhou kiln Northern Song Dynasty celadon vase with stacked pattern, housed in the Yongkang Museum.

- An Ou kiln Song Dynasty green glazed brown painted fern pattern ewer, housed in the Wenzhou Museum.

- A Southern Song Dynasty Guan kiln celadon tripod censer, housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Celadon is diverse

"Qing" is not a simple color, but rather refers to the combination of three colors: green, blue, and cyan. Therefore, the glaze used for coloring ceramics is called "qing glaze".

Based on the colorful qing glaze, Chinese celadon colors include moon white, secret color, powder blue, and so on. As a result, ceramic ware has natural colors like a clear blue sky or green mountains and rivers.

The green color that is tempered in the firing process, with varying shades that can evoke feelings of joy, aversion, delight, or pity, has a beauty that is as deep and ancient as its history.

Primitive celadon and fragments of vessels such as vessels, bowls, plates, vases, jars, and beans have been discovered from as far back as the Shang and Zhou Dynasties 3000 years ago.

Although they already possessed some of the characteristics of porcelain, they still had a primitive quality compared to the mature Celadon of later periods. Celadon continued to develop throughout the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods and made significant breakthroughs during the Eastern Han Dynasty, ultimately leading to the traditional celadon that we know today.

During the Three Kingdoms, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties period, the production of celadon became more common in different regions of China. The number of kilns increased, and the variety of celadon expanded while its quality improved. The southern celadon was translucent like ice, with a pure and sparkling glaze. The northern celadon was slightly yellowish in its green, with a strong glassy texture and delicate crackles in the glaze.

During the Tang Dynasty, based on the development of Qing porcelain in the Sui Dynasty, different styles of porcelain kiln systems were formed in many places, reflecting the prosperity of the porcelain industry and different artistic characteristics, achieving the "flower of porcelain" that was "as jade, as clear as a mirror, and as melodious as a chime". Among them, Yue kiln was particularly outstanding and ranked first in the country.

In addition, during the Tang Dynasty, Qing porcelain gradually replaced lacquer, wood, bamboo, pottery, and metal products due to its superior material conditions, and penetrated into daily life.

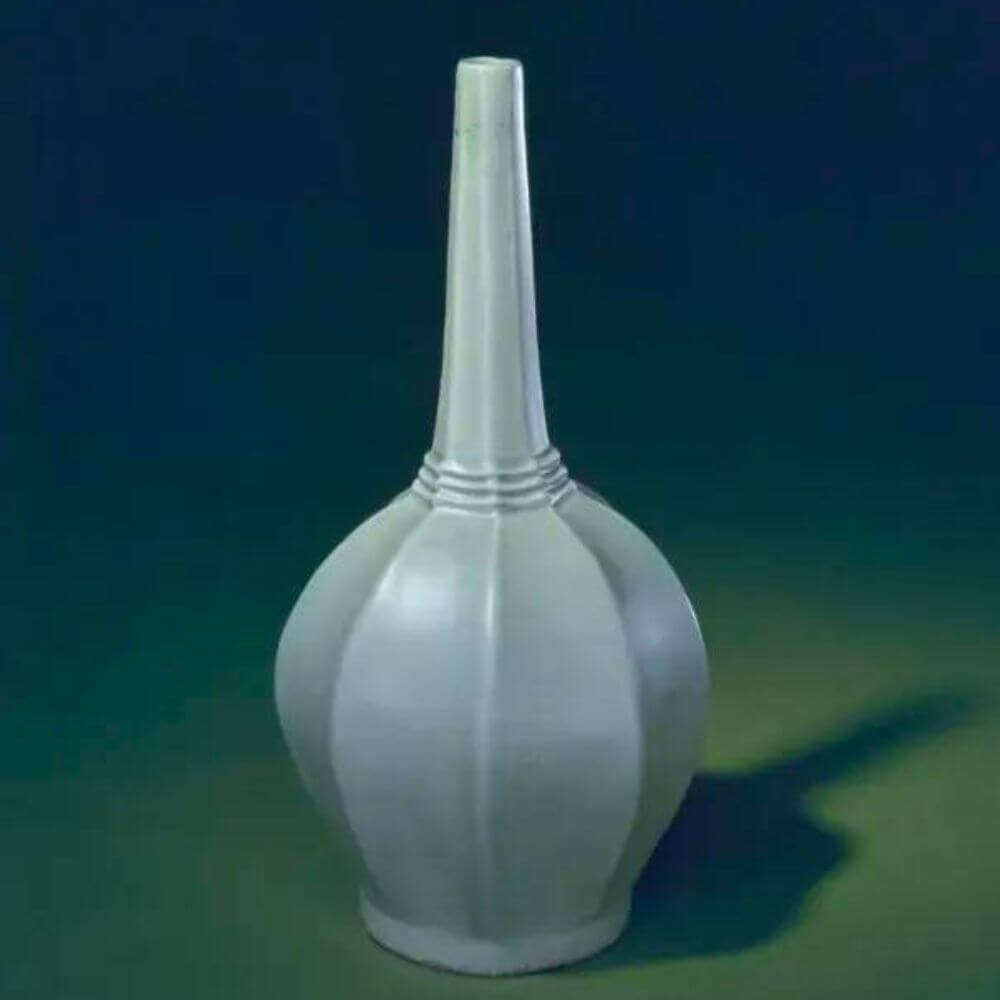

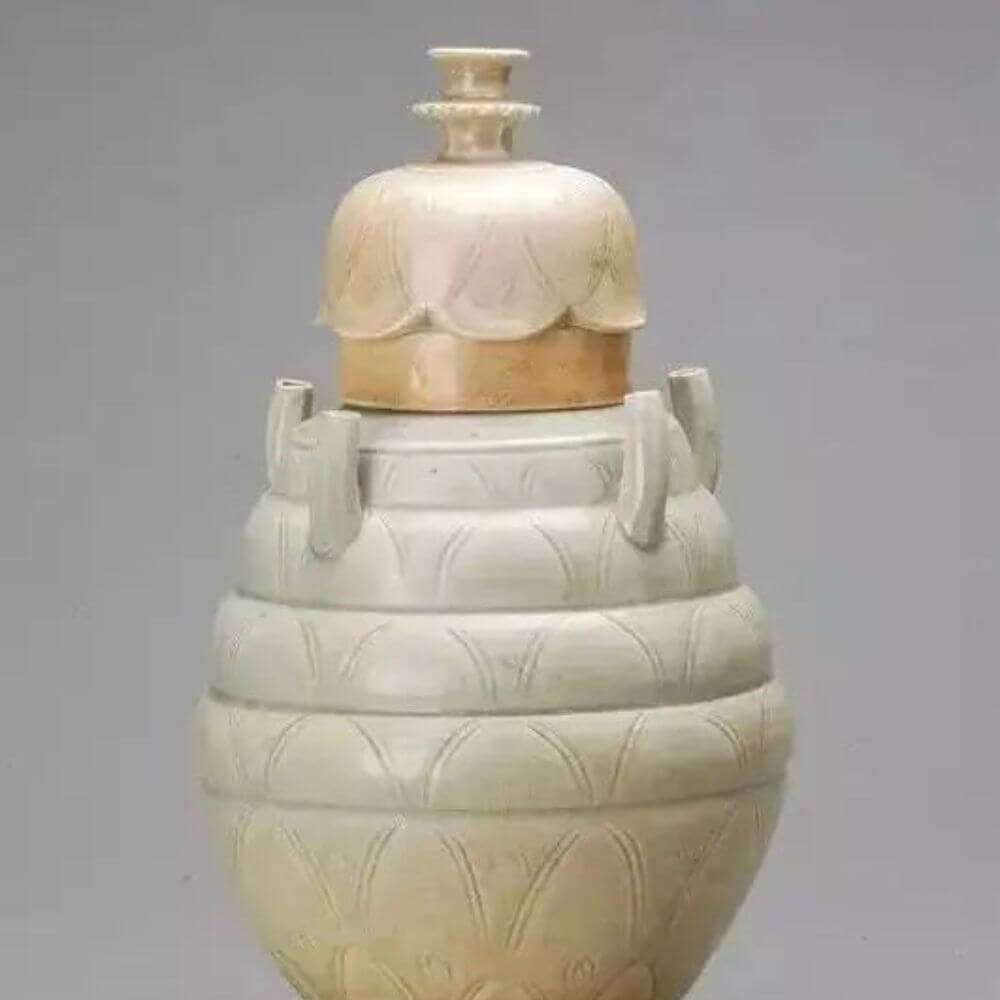

Tang Yue kiln secret color porcelain octagonal clean bottle

The Song Dynasty is undoubtedly a dynasty that cannot be ignored when it comes to celadon. Perhaps it was the social trend of the Song Dynasty that made celadon more charming. Ceramic craftsmen integrated art into their techniques and used shades of green to depict the lives of the Song people. This created a flourishing ceramic industry where "official kilns stand alongside civilian kilns" and elegant shapes and pure glaze colors became the representation and model of ancient Chinese ceramics. Among the famous Song Dynasty "Five Great Kilns," four of them are related to celadon.

Northern Song Dynasty official kiln powder green glaze bottle

From a modern perspective, the firing and development of celadon is a particularly important aspect of Chinese ceramic history, in terms of both craftsmanship and technology. It is a process that evolved from accidental discovery to deliberate utilization.

However, from an aesthetic perspective, we are more inclined to believe that the intention behind the color green was too elusive, and so ancient people used a unique method to solidify it onto ceramic ware, allowing people to appreciate the beauty of green.

What is Kiln Mouth?

But if we further trace the color of celadon, we have to talk about the place of production of porcelain - "kiln mouth".

Depending on the kiln mouth, the porcelain produced there also has its own characteristics in terms of shape and various techniques.

Southern Song Dynasty Longquan Kiln Celadon Phoenix-Ear Vase.

Southern Song Dynasty Longquan Kiln Celadon Phoenix-Ear Vase.

To distinguish these kilns, we generally use three methods to name them:

The first is to divide them by place name. This is the most common naming method, mainly named after the prefecture or county to which they belong. For example, the kiln in Shanglin Lake, Yuyao, Zhejiang, is named "Yue Kiln" because it belongs to the Yue Prefecture. Other kilns, such as Ding Kiln, Longquan Kiln, and Ge Kiln, are also named in this way.

The second is to divide them by dynasty. For example, Tang kiln, Ming kiln, and Qing kiln.

The third is to name them based on their business nature. For example, the kiln in Linhu, Yuyao City, which produced a secret color porcelain that could not be used by ministers and commoners, was named "Secret Color Kiln." The kilns in Bianliang during the Northern Song Dynasty and in Hangzhou during the Southern Song Dynasty, which produced porcelain exclusively for the imperial court, were named "Official Kilns."

Chinese Celadon Ancient Kiln Site

The Song Dynasty is undoubtedly a dynasty that cannot be ignored when it comes to celadon. Perhaps it was the social trend of the Song Dynasty that made celadon more charming. Ceramic craftsmen integrated art into their techniques and used shades of green to depict the lives of the Song people. This created a flourishing ceramic industry where "official kilns stand alongside civilian kilns" and elegant shapes and pure glaze colors became the representation and model of ancient Chinese ceramics. Among the famous Song Dynasty "Five Great Kilns," four of them are related to celadon.

Different kilns produce different shades of celadon.

The reason why celadon can form different shades of green is due to the amount of iron oxide in the body and glaze, which is fired in a reducing atmosphere. The presence of iron causes the glaze to show different shades of green or yellow depending on the reducing atmosphere during firing. The higher the degree of reducing atmosphere, the greener the color appears.

Some celadons contain impure iron, and insufficient reducing atmosphere during firing can cause them to appear yellow or brownish.

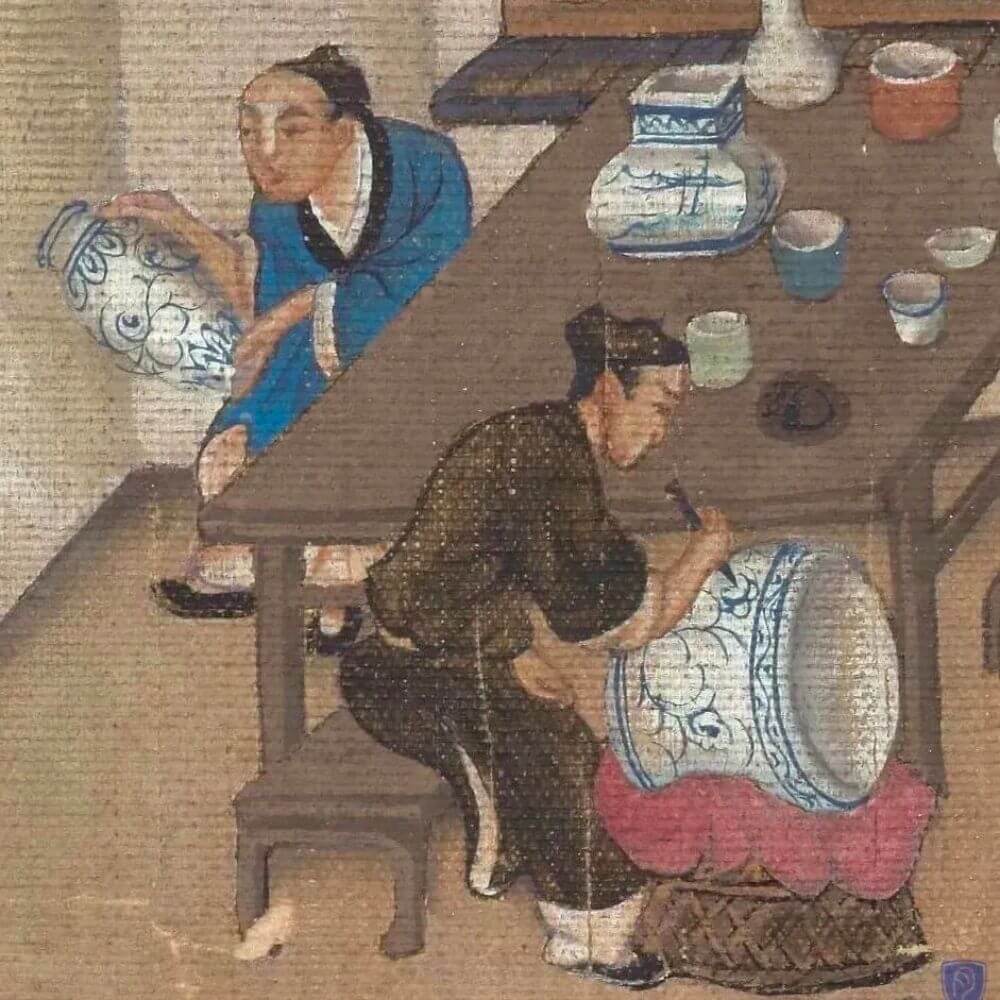

Reproduction of the scene of making celadon in ancient China

The diversity of kiln sites

During the Qin and Han dynasties, kilns for producing proto-porcelain were generally built on hillsides with porcelain stone deposits, mainly in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. These kilns were mostly small in scale and produced both proto-porcelain and high-temperature stoneware. The kiln sites were scattered or clustered in groups of three to five, with the largest groups having over 10 sites.

For example, there were 11 kiln sites in Dadingshan, Shangyu County, and 16 kiln sites in Dingshu Town, Yixing, Jiangsu Province. Dingshu Town was the most concentrated area for kiln sites during the Han dynasty, with two kiln sites in the town and the rest located on the northern foot of the southern mountain, 3 kilometers southwest of the town.

With the gradual scale and standardization of porcelain production, kilns can be classified into four types according to their shape:

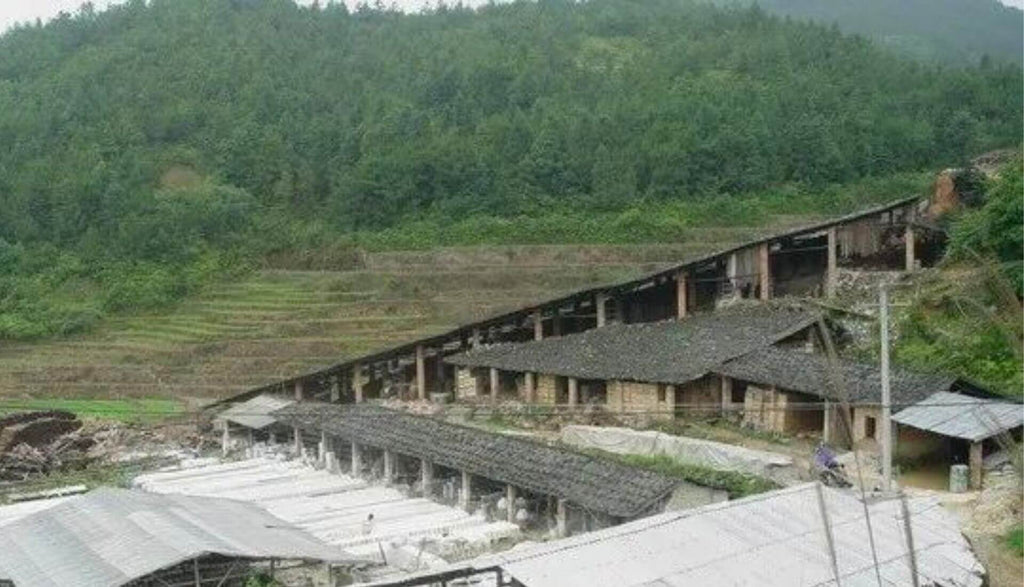

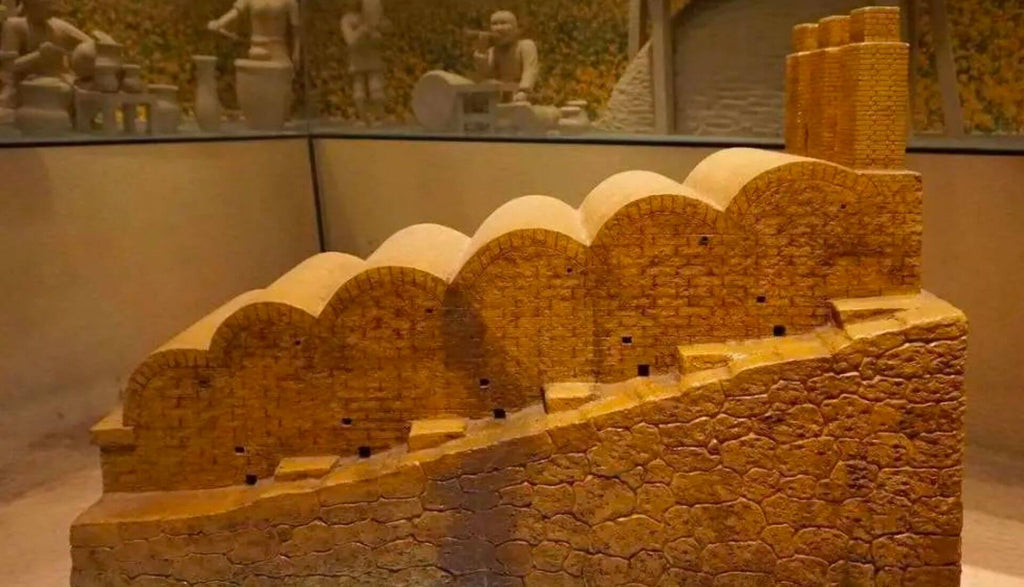

The first type is the dragon kiln, also known as the Chang kiln. It is a semi-continuous ceramic firing kiln that is built on a slope and named after its dragon-like shape. The kiln room is divided into three parts: the kiln head, the kiln bed, and the kiln tail. It has been built with masonry in the southern region of China from the Shang Dynasty to the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

The Longyao kiln, also known as Chang kiln, first appeared in the Shang Dynasty. It used natural ventilation and used plant materials such as twigs and pine branches as fuel. The flames in the kiln mostly flowed parallel to the kiln bottom. As this type of kiln was built on a slope, the flame draft was strong, and the heating and cooling processes were fast, allowing for fast firing and the maintenance of a reducing atmosphere for firing celadon. Therefore, it is said that the Longyao kiln is the cradle of celadon.

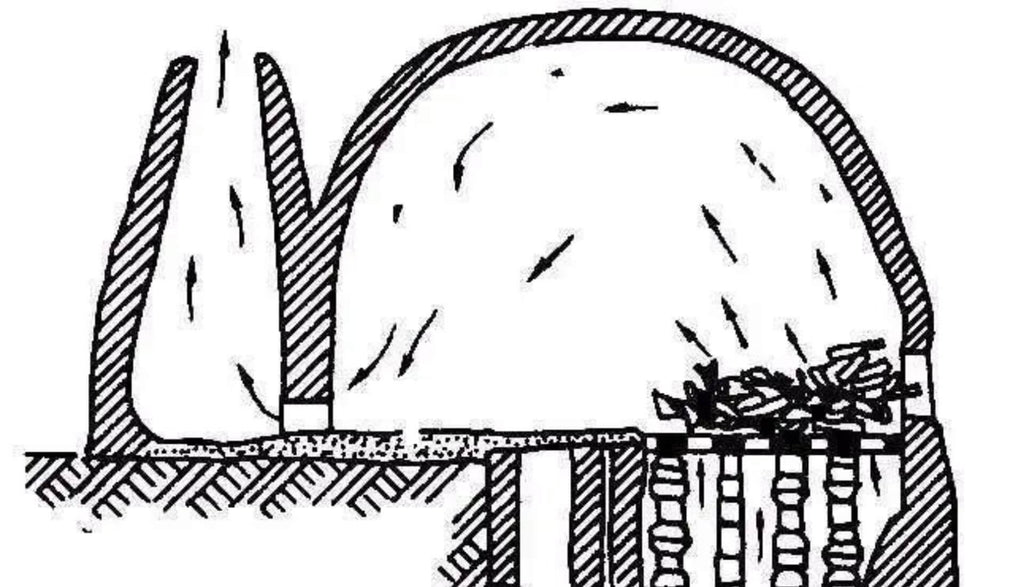

The second type is the round kiln, also known as "mantou kiln", named after its shape resembling a Chinese steamed bun. It is a type of ceramic kiln that originated in the Warring States period and later used coal as fuel, making it the earliest ceramic kiln to use coal as fuel. The round kiln generally consists of a kiln door, firebox, kiln chamber, chimney, and other parts, and is mostly dug out of the natural soil or built with bricks.

The most significant characteristic of the "mantou kiln" is its easy control of the heating and cooling speed, good moisture retention, and suitability for firing ceramics with a thick body and high viscosity glaze at high temperatures. However, due to its relatively slow heating and cooling speed, the firing time is longer, and the temperature distribution in the kiln is not uniform, which makes it prone to producing defective products.

The third type is the gourd-shaped kiln, which is named after its resemblance to a gourd. The Qing Dynasty's "Notes on Southern Kilns" describes the kiln as "lying like a gourd on the ground." It was developed and modified from the dragon kiln, and is suitable for firing ceramics with high potassium oxide content and glazes with high viscosity at high temperatures. It first appeared in the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties, and gradually stopped being used after the appearance of the egg-shaped kiln (town kiln) in the early Qing Dynasty.

Ming Dynasty gourd kiln throwing firewood mouth

The kiln is built using brick or brick blocks and consists of several parts, including the kiln door, firebox, front chamber, back chamber, chimney, etc. The kiln top has a long, narrow waist shape, dividing it into two chambers: front and back.

Jingdezhen gourd-shaped kiln

The stepped kiln, also known as the "staircase kiln," is a kiln with several chambers arranged in a stepped, upward-sloping manner. It first appeared in the Dehua kiln of Fujian province during the Ming dynasty, and developed from the multi-chambered Longyao kiln of the Song and Yuan dynasties. It was introduced to Japan and Korea in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, and is known as the "kushikiln" in Japan. Nowadays, it is still used in rural kilns in Fujian, Hunan, Jiangxi and other regions.

The stepped kiln

The stepped kiln, also known as the "Dragon Kiln" or "Staircase Kiln," is a type of kiln with a stepped structure that slopes upward. It originated in the Dehua kilns of Fujian province in China during the Ming dynasty and was developed from the divided-chamber kiln. The kiln consists of multiple chambers arranged in a staircase pattern, and is typically fired with wood as fuel and uses natural ventilation. It has the advantage of high firing capacity and efficiency like the Dragon Kiln, and the ability to control the cooling rate like the Man tou Kiln. Additionally, it can make use of waste heat from the front chamber to save fuel. It is suitable for firing porcelain with high potassium oxide content and glazes with high viscosity at high temperatures, such as the white porcelain of the Dehua kilns.

After Tang Dynasty greenware became a royal treasure, there was a division between "official kilns" and "folk kilns" at the kiln mouth. As the name suggests, "folk kilns" refer to kilns operated by the people, mainly serving the common people. After the Tang Dynasty, to meet supply and demand, the number of folk kilns increased continuously. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, folk kilns developed even more in terms of production and quality, becoming the production base for greenware commercial trading.

Northern Song Dynasty Ru Kiln Celadon Lotus Bowl

Northern Song Dynasty Ru Kiln Celadon Lotus Bowl

During the Qing Dynasty, the proportion of private kilns far exceeded that of official kilns, and some official kilns even produced their blue-and-white porcelain using techniques and materials from private kilns.

Qing Dynasty Kiln Ruins

Qing Dynasty Kiln Ruins

During the Ming Dynasty, Jingdezhen saw the emergence of kiln operators known as "guangu" who specialized in imitating ancient official kiln ware. The most famous of these kilns was owned by Lu Zishun in the Fuliang kiln area, which produced porcelain of a quality that rivaled official kilns.

Blue and White Porcelain from Fuliang Kiln

The term "Imperial kiln" or "Guan kiln" originated in the Tang Dynasty, referring to the kilns specially established by the court to provide porcelain for the imperial family. Later in the Song Dynasty, Guan kiln specifically referred to the celadon produced by kilns set up by the court in the capital city of Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng) and Lin'an (present-day Hangzhou), hence the distinction between "old Guan" and "new Guan", the former being the Northern Song Guan kiln and the latter the Southern Song Guan kiln.

Part of Wang Zhicheng's "Tao Ye Picture Volume" in Qing Dynasty

In order to provide the imperial family and nobles with the finest porcelain, a system known as "official supervision and civilian firing" was implemented, in which the porcelain was produced by civilians but underwent rigorous selection processes before the best pieces were selected for imperial use. This type of porcelain is known as "tribute porcelain" or "official kiln porcelain".

An official kiln pierced ear vase under the suburban altar of the Southern Song Dynasty

In addition, to standardize kilns, both the Tang and Song Dynasties established specialized regulatory agencies to strengthen central management of official kilns.

A panoramic view of kilns

Yue Kiln

Yue kiln, also known as "Secret Color Kiln," is a famous ancient southern Chinese celadon kiln and one of the treasures of traditional Chinese porcelain craftsmanship. The kiln was mainly located in the area of Yuezhou (now Ningbo and Shaoxing cities in Zhejiang province).

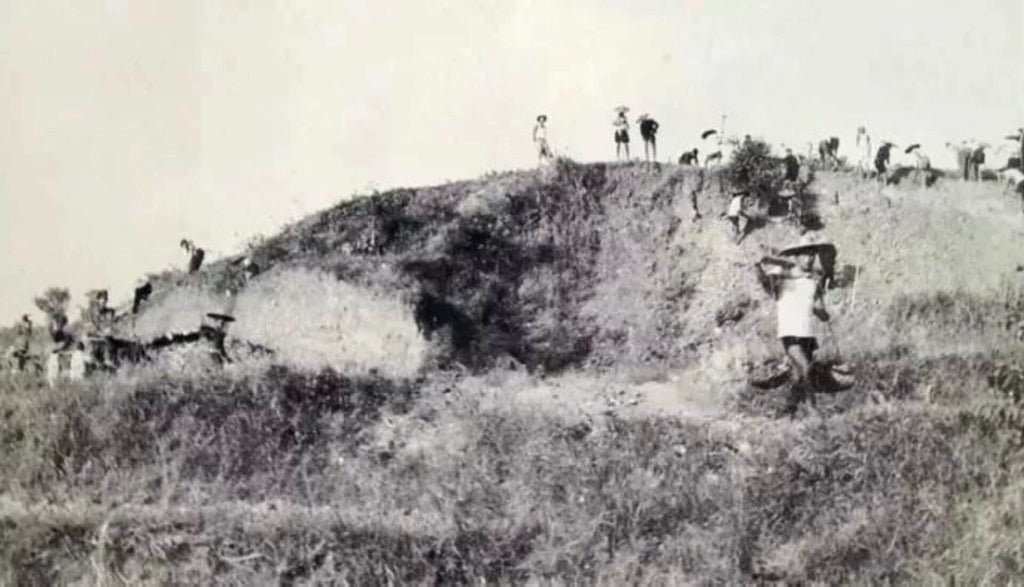

Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Ruins

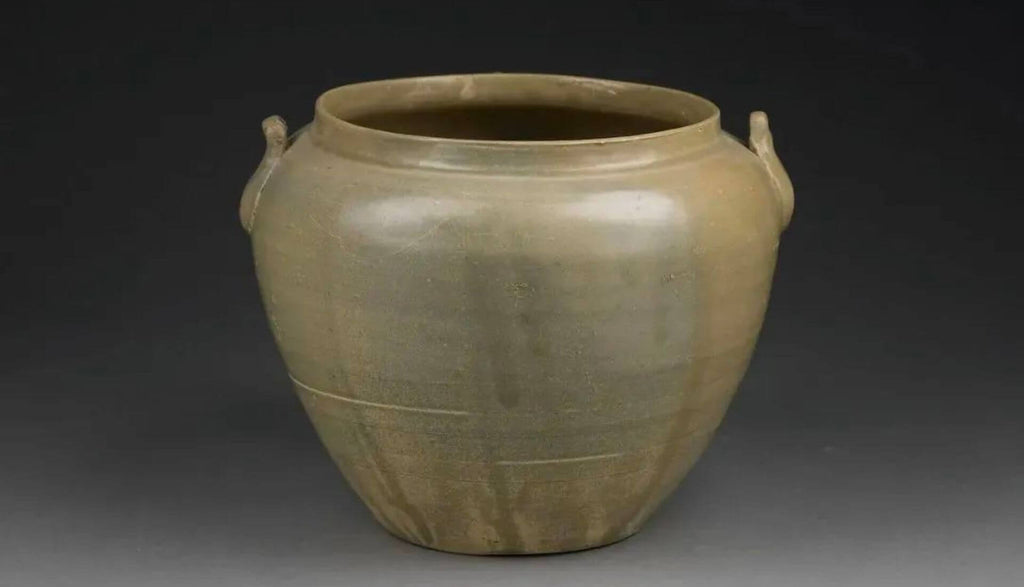

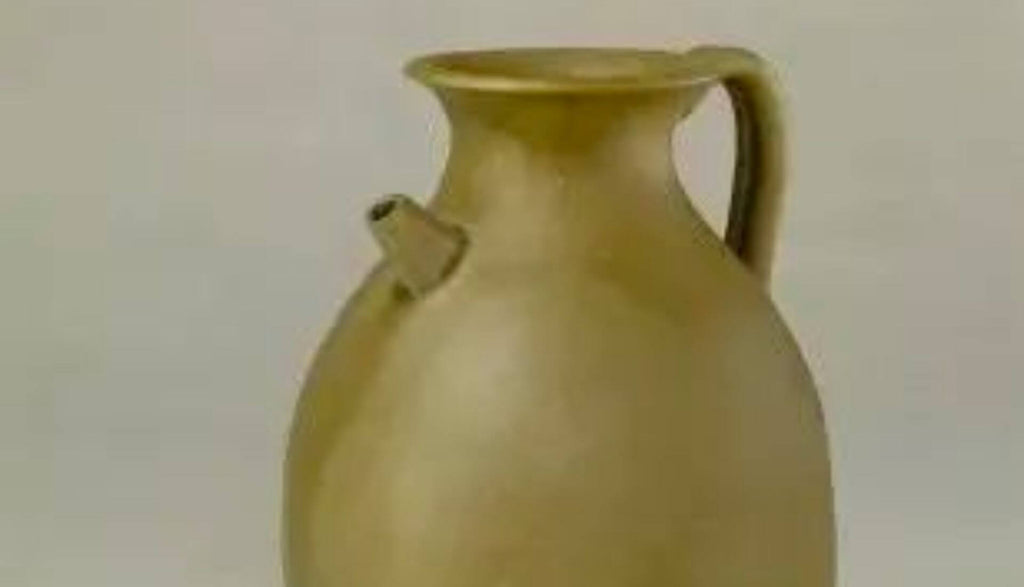

The production of Yue ware dates back to the Eastern Han Dynasty and continued until the Song Dynasty. The Tang Dynasty was the pinnacle of Yue ware craftsmanship, and it was the best in the country. Due to the beauty of its porcelain quality, shape, and glaze color, it perfectly matched the tea-drinking fashion at that time and was greatly loved by tea drinkers. Lu Yu praised it, saying, "Yue and Yuezhou porcelain are both green, and green enhances tea."

Tang Yue Kiln Celadon

Tang Yue kiln green glaze holding pot

Jun Kiln

Jun kiln, also known as Juntai kiln, is a unique style of porcelain that was developed based on the style of the Luoyang porcelain. The kiln emerged during the Song and Jin dynasties and has been widely acclaimed ever since.

In fact, during the late Northern Song dynasty, it was monopolized by the imperial court as an official kiln. On the one hand, skilled craftsmen were gathered from the private sector to produce porcelain according to the court's designs, and on the other hand, various measures were taken to prohibit its circulation among the people.

Ruins of Jun Kiln in Yuzhou, Henan

The basic glaze color of Jun porcelain is various shades of milky blue, ranging from light sky blue to deep blue, and even paler shades known as "moon white". It has a lustrous and elegant blue luster. Its beautiful color tone is unmatched by products from other kilns.

Northern Song Dynasty Jun Kiln Rose Purple Begonia Flower Pot

"The earthworm crawling on mud pattern" (i.e. presenting wavy and irregular lines of glaze marks extending from top to bottom within the glaze) is an important feature of Jun glaze.

The reason for its formation is that the body of Jun porcelain is first fired before glazing, and the glaze layer is particularly thick. When the glaze layer is drying or during the initial firing stage, cracks occur, and later the low viscosity glaze flows into the gaps during the high-temperature firing stage.

Song Dynasty Jun Kiln Bowl

Song Dynasty Jun Kiln Bowl

Longquan Kiln

Longquan kiln, also known as Longquan celadon, was located in the southwest of present-day Zhejiang Province, bordering Anhui and Jiangxi provinces. Its production history dates back to the Three Kingdoms and Jin Dynasty, and it continued to develop during the Tang Dynasty. It reached its peak during the Song Dynasty and continued to be produced during the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, until it was finally discontinued in the early Qing Dynasty. It is the longest-produced celadon variety in the history of world ceramics.

Zhejiang Yongjia Ma'anshan Longquan Kiln Ruins

During the Song Dynasty, Longquan celadon reached its peak in terms of craftsmanship. The celadon produced during the Northern Song period had a thick body, light gray clay, transparent glaze, and a strong gloss on the glaze surface. The decorative patterns were relatively simple, with common motifs such as fish, banana leaves, golden branches, and lotus flowers.

Early Northern Song Dynasty Longquan kiln light green glaze five-tube bottle

The Southern Song period was the pinnacle of the history of celadon ware, and also the heyday of the development of Longquan kilns. With the fall of the Northern Song and the migration of a large number of people from the north to the south, the famous kilns such as Ru and Ding kilns in the north were destroyed by war, but their ceramic-making techniques were introduced to the south. Longquan kiln then combined the essence of southern techniques and northern arts to form its unique porcelain kiln system.

In the late Southern Song period, the successful production of powder blue glaze and meizi blue glaze reached the pinnacle of celadon glaze color beauty and wrote a glorious chapter in the history of Chinese porcelain.

Plum Green Capricorn Ear Plate Mouth Bottle

Guan kiln was a kiln established during the reign of Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty in the capital city of Bianliang (present-day Kaifeng), exclusively for the production of porcelain for the imperial court. The location of the kiln has not been discovered yet. The Tang Dynasty also produced porcelain for the imperial court, which was referred to as "Gong kiln" and was also labeled as "Guan kiln ware."

Guan kiln mainly produced celadon porcelain, and during the reign of Emperor Gaozong, the most popular glaze colors were moon white, pinkish blue, and green. The porcelain body of Guan ware was relatively thick, with a sky blue glaze that had a slightly pinkish tone and large crackles. The unglazed foot of the porcelain was black, and the mouth had a thin glaze with slight visible signs of the porcelain body, which is commonly known as "purple mouth and iron foot."

Song Dynasty Official Kiln Powder Qing Ge Furnace

Due to being specifically established for the imperial court, the porcelain produced at Guan kiln was designed in accordance with palace styles in terms of shape, decoration, and glaze color. Examples of such designs include three-legged incense burners, milk pot-shaped vessels with five legs, double-eared vessels with rounded feet, gu-shaped vases, and gall-bladder-shaped bottles. As a result, the porcelain from Guan kiln has a distinct royal character, exuding an exceptional sense of nobility.

Song Dynasty official kiln azure oval narcissus basin

Longquan Kiln

Ruzhou Kiln, also known as Ju Yao, was named after its location in Ruzhou, Henan Province during the Song Dynasty. According to historical records such as Gu Wenjian's "Fu Xuan Zalv" and Ye Ti's "Tanzhai Bi Heng", the kiln was established due to the poor quality of white porcelain produced in Dingzhou. The Song court ordered the production of celadon wares in Ruzhou, which soon became the most important representative of imperial porcelain during the Northern Song, Southern Song, and Ming dynasties.

Excavation site of Ru kiln site in Qingliangsi

During the early period of the Northern Song Dynasty, the Ru kiln's early firings of celadon had thin glazes and unstable colors, with the glaze appearing pale blue, and the surface had few decorations. However, through continuous improvement during the middle and late periods of the Northern Song, the celadon glaze color was optimized, with a variety of decorative patterns appearing, and techniques such as incised carving and stamped patterns were introduced. It was during this time that the Ru kiln produced sky-blue glaze, which was selected as tribute porcelain, marking its peak period.

Northern Song Dynasty Ru Kiln Celadon Fenghua Paper Mallet Vase

Ru Kiln Piece

During the Song dynasty, there were many ancient kiln sites for firing Ru porcelain in various directions in Ruzhou, forming a prosperous scene of "kiln fires everywhere on both sides of the Ru River for hundreds of miles". At its peak, there were over 300 kilns.

However, after the Jin dynasty conquered the Northern Song dynasty, the production of Ru porcelain declined and eventually disappeared. The kilns only operated for a short period of about 20 years, so there are very few surviving pieces. By the time of the Southern Song dynasty, Ru porcelain was already very rare. Today, there are less than 100 genuine pieces of Ru porcelain that have survived.

A Ru kiln celadon narcissus basin without grain, Northern Song Dynasty

What happens when earth meets fire? Sometimes they clash and one overpowers the other, but other times they create something stunningly beautiful together. Qing porcelain is the crystallization that resulted from their collision, revitalized over generations by skilled craftsmen and artisans.

From ordinary household items to luxurious court utensils, the kilns' flames produced diverse patterns and a dazzling green color. As we step into the kilns where Qing porcelain was fired, we not only feel its history but also experience the continuous sublimation of its beauty across generations. As a magnificent creation of the Chinese nation, it will undoubtedly be worth exploring and studying by more people.

(Only be reproduced with the consent of Celadoner!)